A review of 30 cases of Alabama Rot asks: “What causes CRGV in dogs? Unfortunately, the cause is unknown at the moment, but there is one strong candidate – aHUS (atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome).”

“CRGV disease is a TMA (Thrombotic Microangiopathy – blood clots caused by platelets within the small blood vessels of the kidney) of unknown aetiology”

Alabama Rot is also known as CRGV (Cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy). CRGV is characterised by blood clots in small blood vessels aka TMA. The cause (aetiology) of CRGV is unknown.

So what causes CRGV in dogs? Unfortunately the cause is unknown at the moment, but their is one strong candidate – aHUS (atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome). CRGV causes dogs to have skin lesions and acute kidney injury. When dogs get CRGV they die in 8 out 10 cases.

Download

Download David Walker and others March 2015 paper in the Veterinary Record (VR): The Press Release, a one page summary and the free open-access 13 page complete pdf, published online on March 23, 2015. (1) Also listen to the VR David Walker 14 minute Podcast in March 2015.

Press Release

The Press Release is just over one page length. Key points:

1) “No evidence of E coli shiga toxin, which can cause sudden onset kidney damage in humans as part of a disease called haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) was found in the kidneys or faeces of affected dogs.”

2) “Acute kidney injury in these dogs was caused by damage to the small blood vessels of the kidney (renal thrombotic microangiopathy).”

3) “The pathology is also found in another rare disorder affecting dogs and humans – haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) – which results in acute kidney injury and anaemia, but which is not associated with skin lesions.”

4) “The authors say that it is unclear whether canine haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) and cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy (CRGV aka Alabama rot] are two distinct disease processes, but emphasise that damage to both the small blood vessels of the kidney and the skin seems to be unique to Alabama rot.”

Review by Veterinary Times

Veterinary Times reviews the paper. This includes March 2015 comments by David Walker.

March 2015 Veterinary Record Paper by David Walker and others (13 pages)

Summary by Chris Street of AlabamaRot.co.uk

Introduction

Cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy (CRGV) is a disease of unknown causation [aetiology] which forms ulcers or lesions in dogs legs [distal extremities] and a loss of kidney function within 7 days [Acute Kidney Injury] (AKI). Before November 2012, CRGV was only reported in greyhounds in the USA, a Great Dane in Germany and a greyhound in the UK.

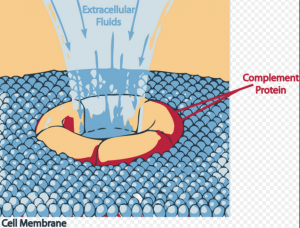

With CRGV, blood clots form in small blood vessels [Thrombotic Microangiopathy] (TMA) because of inflammation and damage to cells that line the inside of blood vessels [vascular endothelium]. TMA leads to blood clots in small blood vessels [microthrombi] resulting in fewer platelets [Thrombocytopenia], destruction of red blood cells [microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia] and failure of the kidney and other organs [multiorgan dysfunction].

CRGV is the only canine disease that causes inflammation and destruction of kidney and skin blood vessels [vasculopathy].

AKI can result from many types of renal injuries. Skin lesions are not normally found with AKI in dogs, unless AKI has resulted from immune disorders [immune-mediated disease], tumours [neoplasms], infectious diseases or vasculopathy (disease affecting blood vessels).

This report summarises the symptoms [signalment], laboratory [clinicopathological] findings and outcomes of 30 dogs seen by vets

between November 2012 and March 2014, in which CRGV was suspected and TMA was identified.

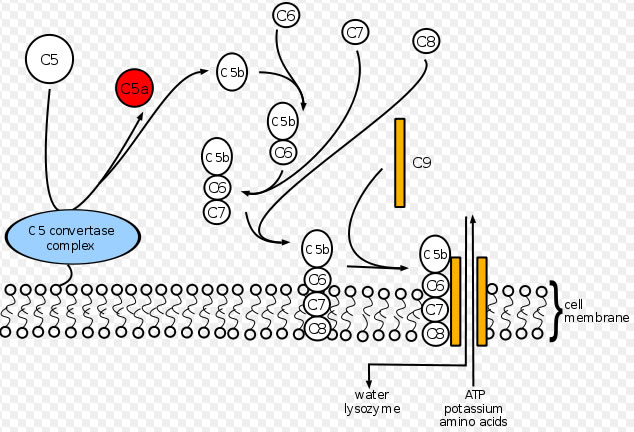

atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS)

aHUS is a human disease often caused by uncontrolled activation of the complement system. CRGV may resemble human aHUS since skin lesions and AKI is found in both diseases. CRGV may be triggered by an environmental or infectious agent:

“In people, genetic or acquired conditions causing complement dysregulation can cause another TMA, known as atypical HUS (aHUS) (Noris and others 2012). Skin lesions have been reported alongside haemolysis and AKI with aHUS (which is not the case with STEC-HUS), but the incidence is rare (Ardissino and others 2014b). Even in patients with multiple genetic defects, aHUS may not develop until adulthood and an environmental trigger is considered likely for the development of disease (Salvadori and Bertoni 2013). Atypical HUS has not been reported in dogs; however, CRGV may bear some resemblance to this disease, especially given the concurrent findings of skin lesions and AKI identified in both diseases. An infectious or environmental trigger for CRGV may be suspected, given the number of in-contact dogs in this case series that developed skin lesions with or without AKI. It was also interesting to note that all of the affected in-contact dogs were related either to each other and/or to a confirmed case.” (page 10 of 12)

Humans with aHUS are treated with the drug Eculizumab:

“A recombinant, anti-C5 antibody (eculizumab) is the treatment of choice for human aHUS (Kavanagh and others 2013, Salvadori and Bertoni 2013) but the cost has prohibited its evaluation in dogs.

Also

“Plasma exchange … is a useful therapy for aHUS (Kavanagh and others 2013).”

I’ve discussed Eculizumab and plasma exchange / plasmapheresis to treat CRGV.

“An infectious or environmental trigger for CRGV may be suspected, given the number of in-contact dogs in this case series that developed skin lesions with or without AKI. It was also interesting to note that all of the affected in-contact dogs were related either to each other and/or to a confirmed case.”

Clustering of Cases

The paper said:

“Human STEC-HUS tends to occur either sporadically or in small geographical clusters (Milford and others 1990, Tarr and others 2005, Salvadori and Bertoni 2013 (2)), which may be similar to the findings in this case series and epidemiological investigations are ongoing. Although cases were reported from across the north and south of England, 36.7 per cent came from The New Forest, Hampshire. This high percentage could, however, be attributed to the geographical location of the primary investigators in Hampshire and increased awareness amongst local veterinarians.”

Is the clustering of CRGV around the New Forest (and possibly Guildford and Manchester) real or apparent? I discuss this here.

Management

The paper said:

Management of human TMA’s is dependent upon the underlying cause. Plasma therapy, antibiotic administration, monoclonal shiga toxin antibodies and renal transplantation have all been used in STEC-HUS. A recombinant, anti-C5 antibody (eculizumab) is the treatment of choice for human aHUS (Kavanagh and others 2013, Salvadori and Bertoni 2013) but the cost has prohibited its evaluation in dogs. Plasma exchange remains the treatment of choice for human TTP (Blombery and Scully 2014) and is a useful therapy for aHUS (Kavanagh and others 2013). Monoclonal antibody therapy to CD20 and classical immunosuppressive drug therapy have also been reported for management of human TTP (Blombery and Scully 2014). One dog with CRGV was reportedly ineffectively managed with immunosuppressive therapy (Rotermund and others 2002). The efficacy of plasma therapy and monoclonal antibody therapy has yet to be evaluated in CRGV.

Eculizumab inhibits Complement C5 cleavage by binding to C5 so that C5 Convertase enzyme, cannot produce C5 and C5b proteins. These proteins are required to produce Complement Membrane Attack Complex (MAC), which destroys epithelium of kidney glomerular and causes skin lesions.

“Eculizumab prevents circulation of the pro-inflammatory C5a peptide and generation of the cytotoxic terminal complement complex C5b-9 (referred to as the membrane attack complex or MAC).”

Could Alexion Pharma UK, the manufacturers of Eculizumab, sponsor trials in dogs with CRGV? I have discussed Eculizumab here.

The summary paper said:

“Known differential diagnoses for canine TMAs include

CRGV and haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS). The

most common form of HUS in humans is associated with shiga toxin-producing bacteria causing diarrhoea (STEC-HUS). However, E coli shiga toxin has not previously been identified in dogs with HUS or CRGV and was not identified in the dogs in this case series. Management of human TMAs is dependent on the underlying cause. The optimal management for CRGV remains unknown.”

Neither Shiga toxin (from Shigella dysenteriae) nor Escherichia coli genes encoding for shiga toxin, were identified. Acute leptospirosis is unlikely says the paper.

CRGV could be caused by an infectious or environmental trigger, given the number of in-contact dogs that developed skin lesions with or without AKI. All of the affected in-contact dogs were related either to each other and/or to a confirmed case.

Other points:

- viruses were not found in kidney tissue but that does not exclude a viral cause.

- is CRGV a novel canine disease or a variant of HUS, aHUS or another human TMA eg thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura (TTP)?

- evaluation of canine complement system may find the cause.

- Management of human TMA’s is by Plasma therapy, antibiotic administration, monoclonal shiga toxin antibodies and renal transplantation – all used in shiga toxin E coli (STEC)-HUS. [see http://www.infokid.org.uk/STEC-HUS – source of UK STEC is faeces from cattle, deer, rabbits, horses, pigs, wild birds.]

- A recombinant, anti-C5 antibody (eculizumab) is the treatment for human aHUS [approved in 2015 by NICE].

- Continued evaluation will give understanding of the disease and identify possible triggers, and determine the most appropriate management.

- [Atypical HUS is not caused by an infection, but rather is thought to be linked to genes http://www.infokid.org.uk/STEC-HUS]

- Is this an emerging disease or, one that was previously present but unrecognised?

Conclusion

CRGV is a TMA of unknown aetiology. If dogs with skin lesions have abnormally high Nitrogen levels (urea or creatinine) in the blood [azotaemia] this means that the dogs’ kidneys have failed and they will likely die. Vasculopathy affects the small vessels of the skin and kidneys in dogs and is unique to CRGV. Continued research will hopefully help to identify possible CRGV triggers and best management of dogs.

Key Quotes

“The question remains as to whether this is an emerging disease or, one that was previously present but unrecognised.”

“Over the first 12 months of the study period (November 1, 2012–October 31, 2013), confirmed cases presented in November (n=2), December (n=2), February (n=4), March (n=1) and May (n=1). The remaining 20 confirmed cases presented between November 1, 2013 and March 31, 2014.”

Note: no new cases of CRGV between June 2013 and October 2013 inclusive.

As per the AlabamaRot.co.uk map this pattern was repeated in June 2014 to October 2014 (except for one case in June 2014 in Lancashire and one case in September 2014 in Leeds).

“Fourteen dogs lived in the same household as one of the 30 confirmed CRGV cases. Of these 14 dogs, two developed skin lesions and AKI and six developed skin lesions without AKI (n=8).”

The paper reported that known causes of AKI were excluded.

Further summary … to follow.

Chris Street BSc MSc

References

(1) Holm, L.P., Hawkins, I., Robin, C., Newton, R.J., Jepson, R., Stanzani, G., McMahon, L.A., Pesavento, P., Carr, T., Cogan, T., Couto, C.G., Cianciolo, R. and Walker, D.J. (2015) ‘Cutaneous and renal glomerular vasculopathy as a cause of acute kidney injury in dogs in the UK’, Veterinary Record, vol. accepted January 21st 2015, no. available free online 23rd March 2015, pp. 1-12.

(2) SALVADORI, M. & BERTONI, E. (2013) ‘Update on hemolytic uremic syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations.’, World Journal of Nephrology, vol. 2, pp. 56-76.

Are there any findings of a hyper, or inappropriate immune response in post mortem or testing of living dogs…maybe to pathogens such as E.Coli, which would normally be immune regulated?